After many years of drama teaching to British high school students (Key Stages 3-5), I have started to put together some of the ideas, themes, warm-ups, games, productions that I have worked through with students. Some are articles published at Suite 101. Some will be unique articles published here. Eventually, some teenage performance/production ideas will be available to download from here.

These are the Suite 101 articles on drama teaching, so far:

Using Masks as a Creative Teenage Drama Tool

First published on Suite 101, 24 September 2011

The mask as a device to support teaching of theatre history, culture diversity and improvisation techniques in Key Stage 4 (ages 14-16), is second to none.

The mask is a versatile object. For protection (industry; fencing), for prevention (infection), for disguise or grotesque effect (to amuse or terrify), for replication (humour, satire, identification), it has many forms. In secondary drama, it can be the teacher’s friend. It helps narrate tales, sets chilling scenarios, heightens comedy.

Teenage girls often dislike some kinds of masks, notably clown faces and heads. Many of both sexes dislike the claustrophobia of masking, so a simple, symbolic mask on a stick serves some of the learning potential.

Masks for History

Masks have been around for thousands of years, evidenced in wall paintings, pottery and ancient documents, often embedded deep in ritual. They have been, and still are, seen in theatre, dance, opera performances; initiation rites/ceremonies and as works of art. Studying Greek and Roman theatre history as origins of western tradition, for instance, is enhanced by simple masks.

Japanese Noh theatre masks are generally neutral in expression. Actors’ skills must bring them to life in an often subtle way. That’s a hard one sometimes for youngsters, but worth the effort. There are mask traditions in ritualistic theatre across China, India, Java, Tibet and Sri Lanka (Ceylon until 1972).

Ancient Egyptians used mummy masks, with the death mask becoming a physical representation of the belief that the soul needed a safe journey into the afterlife. Similar cultural tradition is found in Ghana and Zambia. They are widespread across the history of peoples in both North and South America.

The commedia dell’Arte originating in the 15th-17th centuries in Italy relied exclusively on physicality and acrobatics for highly developed improvised humour. Their masks became identified with particular characters, so they’re worth teaching in theatrical antecedents.

Masks for Religion

In a multicultural society, it’s impossible to teach drama without being aware of the impact of different religious values on teenagers. Theatrical links with religion are proved in most cultures, from Egyptians, Celts, Greeks, Slavs. Both pagan and Christian roots are evident in many festivities. Halloween, witchcraft trials, Mardi Gras, Notting Hill Caribbean festival have easily accessible images for young people.

Mask origins/functions are complex and varied. Character disguise or dramatic effect are fundamental to drama and a creative opportunity. A mask does not have to be thought to embody a spirit, but it will always transform the wearer, psychologically or in a spiritual sense.

The impact on audience, either the class or a full one, is incalculable. The shock that an Artaud style treatment gives a performance piece, is magnified if the group wear appropriate masks. In simple terms, pose the questions: what lies behind the surface of the person? Of our society? Why do we hide behind masks?

Highwaymen and thieves, rapists, terrorists, kidnappers, the disfigured, the robotic, the psychologically disturbed, the clinically insane, Ku Klux Klan, executioners, purveyors of magic and dreams are all well served by masking. Toby Wilshire of Trestle Theatre Company said: there is a magic surrounding masks, but I believe it’s in the audience perception of the mask, not the mask itself’.

Others see the mask as a form of metamorphosis/transubstantiation for the wearer, not just putting up a face block. There is a difference between controlling the mask and being controlled by it. Students should grasp that. They have to work harder physically to convey expression and meaning when masks take away their facial and vocal communication.

Masks for Devising

Drama Teaching has a simple starter student mask lesson. A Trestle schools mask workshop uses the following or related exercises. Get students to imagine a piece of string attached to the nose is leading you round the room. It’s in charge, it leads wherever. ‘Now you have become a creature that is all nose. What are you like?’

Ask them to make a face not their own, that they can hold. Find a voice for the face; then a body for the face and voice, then simple movements for face, voice, body. This whole creature is a mask. Then in pairs, as these ‘characters’, improvise a tea break at work, or a job interview. Exaggeration, even comedy will ensue.

Next, build the idea that a character wearing a mask must always be facing audience directly. experiment with paired scenes, using mime only, but where they both face front. Periodic discussion is essential to carry them with you. The dead-pan, cheap, thin plastic type masks could now be used to repeat scenes just made up.

Then, still in neutral masks make scenes sinister, a nightmare. Reduce lighting if possible; add music. Already the power of mask and setting should be apparent.

They are ready to try exaggerated character masks, like a set of Trestle ones. Lay masks on floor, let a small group wander around them, then choose one each. Never let them mask-up facing audience; turn backs and spin, using the character in the face to determine posture.

Movement must be bigger than life. Build a family tableau, add narration, let each one add a verbal caption. Get audience to contribute comment. Replace performers one at a time from audience, so same face now has a different body. It’s all about trial and error. When the face doesn’t move, people look more at the body.

Masks for Depth

It may be that a little taster is all a class can take. However, many go deeper. Trestle masks are expensive, but worth every penny and could supply ideas for a whole term. Let students’ imaginations have free rein. Some will be ready to try other masks then.

The clown is both comical and spooky, which is ideal for teenagers. The hospital mask, the politicians’ caricature, animal heads, gas masks and respirators are excellent for experimenting. Gauze, dark sunglasses and bandages serve the hidden-personality purpose. Let them make their own from big paper bags. Just what is somebody hiding behind a mask?

Stanislavski said: ‘actors can be possessed by the characters they play, just as they can be by masks’. Masks grip teenagers, and can be beautifully linked with things like death or interrogation-torture in drama work.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Using Interrogation-Torture for Teenage Drama Work

First published on Suite 101, 8 September 2011

Asking questions of unwilling people is central to teenage improvisation. Good-cop/bad-cop scenario taken further with a little muscle, that adds interest.

While some may think teaching teenagers drama is torture enough, the sad fact is the news is periodically full of torture, abuse, questioning victims. Whether it’s countries in the west or discoveries in the ‘Arab spring’ regime-changes of current times, there’s plenty of material, film evidence, verbatim reports and witnesses to draw upon.

From history, there is a rich supply of similar material from two world wars and subsequent conflicts, from dictators and tyrants who brooked no dissent and what was done in the name of religion. Killing fields, internment camps, dungeons, torture racks, mass horrors litter the pages of history, including The Bible.

From the fantasies of fiction in book and on film, equally, there are caseloads of scenarios that can inspire and inform work on interrogation for teenagers. What follows is but one suggestion for UK Key Stage 4 (14-16 yrs).

Warm Ups

These are general ideas, to get students used to dramatising questioning. In pairs: a teacher questions a lying teenager, or police officer an awkward suspect. Then redo the one they liked better, so each character shares private thoughts aloud. This prepares later opportunities to share real suffering with an audience.

Still paired, any quick scene in which A lies to B, and gets away with it; and B tells the truth to A and regrets it. What are outcomes and consequences? Again, redo one to get a character to share thoughts aloud.

A short extract from Pinter’s The Birthday Party is useful. Goldberg questioning (and confusing) Stanley is a good taster. This can be expanded for the more able through improvisation into an imaginary psychiatrist scene: questioning somebody about what is deep within. If anything.

Still with Pinter, Mountain Language shows the terror of invading soldiers brutalising surviving women. The short scene where the old woman has had her thumb bitten nearly off by a dog and is asked to ‘name the dog, and I’ll have him shot’ is both comic and unbearably sad, simultaneously.

Later on, for more advanced students, a study of Pinter’s play One for the Road is repaid by a chilling study into physical and psychological torture.

Developing Ideas

Say to the class: ‘Here’s a photo of a middle-aged, gentle-looking man who is granddad, kind to animals and gives to charity’. When they’ve looked, say: ‘and here’s one of a drug man, who has teams of people giving drugs to kids at school gates to hook them…’ Pass round the same photo, demonstrating that people have many faces.

Written extracts from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four (1948) or the movie (1984) show the rat torture in Room 101. The interrogation of Winston Smith on the rack is graphic without being too upsetting. ‘How many fingers am I holding up?’ Four’ ‘And if the party says they are five…?’ It encapsulates brain-washing regimes perfectly.

Try developing characters who are believable in their torture work, still in pairs. Torturers out for a social drink, talking about their work; a torturer and friend who doesn’t know the job the other does; two victims of torture comparing notes (danger of comedy with exaggerated claims, but worth running); old torturer and victim on a healing and reconciliation programme.

It’s possible to research interrogation instructions used by the Nazis, Stasi, Japanese in the war, Russians, CIA, Serbs, Mafia, Saddam Hussein, the Gaddafi regime… things like, ‘come in the middle of the night, no sleeping/eating patterns allowed, exposure to heat/cold, slapping, shoving, standing hours on end, drip on the head, bag on head, play on victim’s fears for his/her family’ all serve to fire dramatic ideas.

If further stimulus is needed, try Kafka. In the Penal Colony: the torture implement of needles slowly printing the crime on the victim’s back being demonstrated; and for the more squeamish, from The Trial, the futility of waiting for years (torture) for a door to open for someone to find salvation, but it’s closed before he realises he was to go through.

Discuss the Issues

The beauty of this controversial topic is the discussion it enables in understanding (minority) views of others, the effects of mental and physical violence, bullying and aggression and the benefits of tolerance and democracy. The actual violence does not have to be shown; students can simulate it, do it in ‘slo-mo’ or have it reported by other characters, which is particularly effective.

If there’s an opportunity to work with history and/or art staff, Goya is compelling. Nicholas Pioch of WebMuseum, Paris explained that Goya (1746-1828), first of the 19th century realists, was a Spanish painter whose work ‘reflected contemporary historical upheavals. He was known for his scenes of violence’. He could also paint charming portraits.

In 1792, a serious illness left him deaf and isolated. Pioch said he became increasingly occupied with ‘fantasies and inventions of his imagination and with critical and satirical observations of mankind’. Get as far as this, and most teenagers will be hooked.

The film Goya’s Ghosts (2006) had an interesting pedigree, explained by executive producer, Saul Zaentz in 2010. Director Milos Forman had wanted to make a film about Goya fifty years earlier, as a student in Communist Czechoslovakia, when he also was taken by a book about the Spanish Inquisition (and noted parallels with communism) and ‘an incident when someone was falsely accused of a crime’.

Having worked together in One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest (1975), they visited Madrid’s Prado Museum to see Bosch and Goya works, and so the movie was envisioned. The ‘moral and religious guardianship’ of the Inquisition was equally fascinating, with the damage it inflicted in keeping people ‘pure for God’. The young girl (played by Natalie Portman) accused of heresy was the third element. The Inquisitor became her only hope of fighting the accusation. ‘And then the horrors began’.

To any who doubt that this is too realistic, violent or inappropriate for teenagers, it does work. Just as almost anything, from death to the Olympic Games and from practitioners to history itself can inspire devising drama, so will this.

But if all else fails, comedy can be called up in the Monty Python Flying Circus (1970) sketch. In this, the real Inquisition was parodied with the repeating punchline: ‘Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!’.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Using History and Arts to Create Teenage Performance

First published on Suite 101, 27 August 2011

Both teachers and teenagers fight shy of history (it being anything from 5 years ago to prehistory) and drama. Yet history is a rich seam for performance.

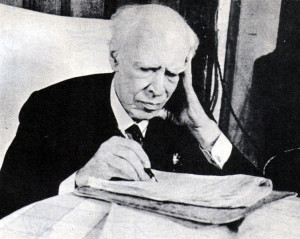

John Fines (1938-1999) was a practitioner who used dramatic techniques to teach history. Steeped in studying the past in an academic way, he had a sudden realisation that the teaching of history should involve children directly with the experience of meeting people from the past through the record that they left behind.

The University of Exeter described him as an expert teacher who drew upon an extensive range of teaching strategies, among which was ‘historical story telling, a way of bringing children face to face with people of the past’.

This plan is designed for UK Key Stage 4 (14-16 years). It acknowledges history as living and when harnessed with other art forms, makes a successful drama and performance project.

The First Step

Take a slice of history. True events, people or places can be localised. A particular house may still be occupied, a site may have become something else. A gravestone may exist. A link with a murder, suicide or something a bit edgy is a head start on appealing to the teenage mind.

Old or former theatres, cinemas, prisons, workhouses, hospitals, pubs, restaurants, stations, hotels, harbours, factories are good starting places. Diaries might survive. The birthplace or death-place or setting for a crime whets appetites, and usually has records to support research.

Ghosts can be effective, although the historical basis may be tenuous. A lost baby, time in a lunatic asylum or the site of a fire/drowning/execution/shooting or hanging, all lend atmosphere. There is much site-specific theatre about that draws on history.

Any one of these events/people/places, the main stimulus, can be introduced by factual evidence, or turned into a piece of improvisation and set in a modern context, to grip with the human drama, before the depth of the history is tapped into. Or go straight for the history, finding real past people and understanding their lives and tragedies.

The Second Step

Take art works inspired by the event/person/place. Paintings, etchings, litho-prints and drawing are a rich source of historical commentaries. Photography and film opened a new vista on safeguarding historical perspective.

Check grand houses, museums and galleries, newspapers and magazines. In April 2012, the centenary of the sinking of The Titanic will be marked. All the victims came from some community, somewhere.

Plays, movies, diaries, court records, songs are made about key events. At executions, songs were often sung marking the reason for the occasion. Ballads arose from tragedies (rail crashes, floods, war time losses).

Specific days, locally and nationally, are good pegs. There is Remembrance Day (around 11th November every year) celebrating wars since the First World War. January sees Holocaust Memorial Day. Bonfire Night (5th November) marks a specific act of terrorism planned but thwarted in 1605 to blow up the Houses of Parliament.

The Third Step

Take an arts practitioner with a distinctive style. Stanislavski with his system (‘Now I am somebody else’) or Brecht with his demonstrating acting (‘Now I am being somebody else’). Artaud with his ‘theatre of cruelty’, getting the audience to confront their demons, is a winning one.

If it is to be melodrama, circus, thriller, sci-fi, comedy, rom-com, musical theatre, satire, surrealist or political, there are books and articles to assist in devising a framework. None of it should be too restrictive, it’s a framework for collaboration and creativity.

One Example

Take student instinct to work on revolution, rebellion and regime change. Perhaps some student has fled from a country where such unrest has occured. Or somebody is struck by the human tragedy of just one person that went on, almost unnoticed, during the uprisings.

Take the French Revolution (1789-99) as a stimulus to explore issues, ideas and feelings. The painting by Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, (1793) is a superb visual opener. The artist was in sympathy with the revolution, elected a deputy in Paris, voted for King Louis XVI’s execution and signed death warrants for over 300 ‘enemies of the people’.

His friend was fiery Revolutionary orator Jean-Paul Marat who suffered from a disfiguring skin disease requiring him to sit hours a day in his bathtub. A young Royalist, Charlotte Corday, tricked her way into his apartment on 13 July 1793 and stabbed him. David had visited him only the day before, so recalled every detail of the room for his painting.

The dying man, eyelids drooping, head on shoulder, pen in hand and peace after suffering make this a murder picture of evocative imagery, a dramatic interpretation. Such are the great ingredients of teenage drama: pain, trickery, murder by a young woman and death. It‘s also inspired adults.

Peter Weiss wrote a play, Marat/Sade, The Persecution & Assassination of Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, in the 1960s. First performed by Royal Shakespeare Company, it’s a clever, twisted play within a play, drawing on the Terror of the Revolution as well as the popular practice of public watching performances and behaviour by lunatics in asylums.

The play itself is fascinating as a large cast spectacle. But if directed in the style of Artaud, as ‘a societal psychiatric treatment’, then a new dimension is encountered. Artaud explored the audience in the middle of a swirling vortex into which a performance could explode.

Peter Brook’s 1967 film of the play was described by Fright.com as ‘infamous’ and ‘one of the screen’s great depictions of unfettered insanity, as well as a historical drama with definite contemporary relevance’. It’s confrontational, provocative and stunningly filmed; ideal for teenagers.

So one incident gave rise to many creative works in different genres. Almost any historical subject is suitable for researching, making and refining performance drama with young people.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Using Artaud as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

First published on Suite 101, 1 August 2011

The dark side of Artaud – writer, actor, painter, addict, mental patient – naturally appeals to teenagers. Harnessing some, makes for great drama.

The study of French genius or madman (depending on viewpoint) Antonin Artaud is often left to Key Stage 5 (ages 16-18). However, there is little reason, except perhaps some squeamishness, to steer clear from him in the GCSE years.

To prepare the ground, some discussion of three contemporary questions will be helpful with students. Does violence on TV, video games and in film, encourage copycat and further violence? Is man a savage under the skin of his/her outward rationality? (Think the Lord of the Flies story here). And is violence worse in males or females?

By way of warm up in the practicals, make largish groups and invite them to choose either Romeo and Juliet or Macbeth, reduce the story to the bare bones to tell it in mime/movement, minimal words and in two minutes. After sharing, discuss about the blandness of it, the jumble.

The Shock

Ask: how could they make the audience sit up and take notice? How to surprise or shock watchers? Lights? Sound effects? Exaggerated movement? High volume? High speed? Now they are beginning to see the requirements of Artaud’s ‘Total Theatre’.

Go back to the Shakespeare, and ask them to focus on one heightened moment, like Juliet’s distress at Romeo’s exile, or Macbeth’s anguish at murdering Duncan. Find extreme physical ways of expressing the emotion. Whole group symbolically? Aggressive voices of conscience?

They must experiment. Artaud’s theatre sought to effect a spiritual change in the audience by reflecting their secret crimes/obsessions/hostilities to release their inner energies, to cleanse them, release them of their guilt. Some students may switch off at this point, but most won’t.

Sometimes a handout summarising Theatre and Its Double, Total Theatre and Theatre of Cruelty is useful now. They need to know that some of the influences on Artaud included surrealism, oriental theatre, Balinese theatre, drugs and psychoanalysis, masks, sterility of social drama, magic and myth, colour, rhythm, ritual, ceremony and spectacle.

Artaud was a Dadaist, a movement that arose as reaction to the meaninglessness of war. It was an anarchic response to officialdom and the Establishment. So he reduced the domination of text to a new language between gesture and thought. He homed on vocal flexibility, chants, drones and exclamations. He not only shocked, he wanted to disturb.

The Scream

Get students in a standing circle, start to breath in unison, then cannon, then unison again. Try sitting, kneeling, lying to make different breathing sounds. This can be extended to groans, cries, moans and laughter. Whatever technique used, get a whole class ritual feeling with this drama exercise.

Artaud said: ‘In Europe, nobody knows how to scream anymore, they have forgotten they have a body on stage, they have lost the use of their throats’. As a primal experience in freeing the actor, take The Cenci (1935), and use it to build a scream.

‘Collona comes to the guests, each moving in a small circle closing in a spiral, she makes larger circle around. 10 seconds. The men are the whirlwind, outside the circles. The women are in heap in centre, each struggling with ghosts or demons. Scream’. Have some fun experimenting with that!

Take nonsense words: klaver striva/cavour tavina/scaver kavina/akar triva, and again, experiment with voice, gestures, movement and musical instruments. A 1917 surrealist poem, Karawane, by Hugo Ball is a superb exercise in the bizarre. Artaud moved as far as possible from Stanislavki’s psychological character-led drama.

The Spurt of Blood

A poem by Artaud, Rite of the Black Sun, is another basic text that can be used to try different textual, vocal interpretations. The idea of sick choral poem is powerful. Rhythms are usable with both percussion and body beating.

There is material available about the reality of Artaud’s acting of a plague victim, which conveys both more of his theories and allows ideas from students to be explored and developed. The violence inherent in much of his work can be minimised somewhat, if preferred. Peter Brook’s famous Marat/Sade, available on DVD, is a study in some Artaud techniques.

The short, surrealist, obscure play The Spurt (Or Jet) of Blood is one of his few actual scripts to survive. Strange, it certainly is. To stage it remains one of the great theatrical challenges, although modern technology helps.

There are several versions on YouTube, which can also serve as an introduction to the practitioner. It’s an anti-rational, incoherent story, just primal states (love, sex, death). Its noisy and nasty theatrical techniques were meant to liberate the audience subconscious! If it is remembered that it was written between the world wars: ‘God has deserted us and the world is a violent and shocking place’, there will be more acceptance.

If not, no matter. It is a fun and challenging topic to offer teenagers which should get them to stretch their imaginations to breaking point. Brecht’s ‘making strange’, it isn’t. Neither is it Stanislavski’s Emotion Memory. Artaud is entirely unique, and that is what excites many KS4 drama students.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Using Stanislavski as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

First published on Suite 101, 1 August 2011

The ideas behind ‘system’ or ‘immersion’ acting are invaluable to teenagers as they work on characterisation rather than roleplay.

Instinctively, KS3 (ages 11-13) students tend to roleplay. They act out being parent, teacher, celebrity, without depth of character required by the end of KS4 (ages 14-16). Using some of the techniques articulated by Russian theatre director Stanislavski (1863-1938) helps.

His ‘system’ later gave rise to ‘method’ acting and other styles where actors spend a long time observing, imagining and creating a character that is totally believable in any situation. In every sense, the actor becomes the character.

A promising small group warm-up could be: ask them to fall out over something, so it becomes unpleasant, uncomfortable, ugly and realistic. After sharing those, ask one from each group to explain how he/she felt while acting. Was there believability within?

Imagination and Belief

Stanislavski imagined a world of play and character. He took objectives, circumstances and the ‘magic IF’. Start with solo set-ups: imagine you are a chair, adopt shape, what do you feel, see, hear? Describe accurately. Try it as a television. It will seem strange at first, but is worth persevering with.

This progresses: imagine you are a bean in a tin. In pairs, go on: a conversation between a hammer and a nail; a blade of grass and a shoe; a toaster and a slice of bread. Back in solos: sit on a chair as if it were a throne, a burning radiator, messy. Sip from a cup as if it’s too hot, bitter medicine, unexpected.

Point out that imagination needs factual knowledge, it cannot work in isolation. Get a volunteer to describe their bedroom in fine detail. Get them used to observing (people, places), because they need reality and truth. Not all old people walk with a stick.

As teacher you could (having pre-warned the best student) suddenly burst into an act: ‘Oh, no, I didn’t take my medicine… why didn’t you remind me?’ Throw a panic attack, and argue with the student. It works wonders as exercise in reality!

If an actor believes, the audience will, said Stanislavski. Pass an envelope round the circle with blank paper inside. In turn they open it and read, as if it’s a job loss, winning prize, letter from lover, bank statement. Pass objects round that must become something else. Imagination all the time.

The ‘magic IF’ demands: what would I do in this circumstance. Try some entrance/exit pieces. A character comes from a believable place offstage. How do they make it believable for audiences? Or leave into a place that must be believable.

Emotion Memory

Anything triggers emotion memory, good or bad. Have students sit in silence and recall a smell, mood, action, taste that stirred emotion. How to convey that which is within to an audience?

Solo, walk suddenly from chair across the room in anger, sitting in that mood. Then, happy, sad. That was the outward sign. They need to find a memory that really made them angry (happy, sad) and relive it totally. Try the moves again.

If the teacher feels comfortable with the class, a personal event of deep emotional significance could be shared. Some students will share too. It’s powerful material, if they’re willing. It builds characters.

This leads to the need for absolute concentration. One exercise is have the whole class as workers on a building site, each engaged in their work. Let it run for ages without further input, then stop; ask them to respond to questions in character.

All recite a nursery rhyme while you call out numbers to be added in the head simultaneously. Get a volunteer to tell a story while being distracted by others. Then, work on characters by each having a specific goal.

In pairs, A is outside a corner shop looking in window, B arrives. First work-through is: A’s goal is to choose something in window; B’s is to ask directions. Next one: the shop will shut in two minutes, and B must get to a job interview in 2 minutes, now repeat/develop scene. The teacher can develop this endlessly (most dangerous part of town, A is going to steal from shop, B is suspicious).

Super-objectives

The theory is that if all actors are committed, a sense of truth is born. People in life have objectives that often run counter to others’. A whole class exercise demonstrates, but the teacher must feel the class can handle it. Give each student without others knowing a different super-objective.

For example: you are OCD and want to get rid of all rubbish/mess; you want to make a work of art with furniture; you want to invent a game, you are cunning and devious; you have Bossy Boots Syndrome and want everyone in a straight line; you own everything and will guard it violently; you want everyone in a circle telling life stories, you are a perv; you want to share problems with others, you are insecure.

You are a clown, try to make people laugh; you are inferior, hide in corners; you want perfect harmony and peace; you are a do-gooder; you want everyone to worship you; you want to find your mother; you want to be left alone… and so on.

Totally contradictory objectives leads to a chaotic, stalemate session with furniture everywhere. It can be great fun, but shows how people constantly strive. A good piece of homework is to prepare a monologue using emotion memory. That way, students have time to get into it.

This can be developed into a test: they must come with a character study that they have immersed themselves in all day, and share it with others. As students tend to fall into the Brecht or Stanislavsky type acting naturally, if they have done Brecht or go on to him, the essence is: Stanislavski’s actors say: ‘Now I am somebody else’; while Brecht’s say” ‘Now I am being somebody else’.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Using Brecht as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

Few works of performance are unaffected by Bertolt Brecht’s ideas. To give students a good Brechtian grounding in Key Stage 4 is useful for exams later on.

It’s probably not a good idea to launch straight in to Y10 drama lessons early in September and announce that you are about to teach ideas from a German Marxist playwright who died in 1956. A more devious approach is preferable with teenagers.

A drama lesson along the lines of what they have grown used to in Key Stage 3 will be fine. It’s just the way that the material is shaped that makes Brecht such a good practitioner for students to consider. Certainly if any of the works of, say John Godber, are to be studied later, an intro about Brecht is essential.

A warm-up of creating group still images of inanimate objects (table and chairs, motorcycle), followed by critically analysing the positions and postures is good. Then do one depicting human relationships; make a group of like-minded people (teenagers; pensioners; football supporters) sending signal to outsiders: keep out.

Making a Point

Ask them to think about body language, attitude, gesture, imagine what they would wear. Create three defensive still images, then make one of group outsider trying to join group in three new images. Repeat, highlighting the outsider more. Make a short scene to emphasize the outsider still further.

By now you have something to go on to begin to explain ‘getting a point across’ that can lead to gestus (gesture plus attitude in a character) and ‘making strange’ (verfremsdungseffekt). Audiences usually become involved with the emotion in a narrative; actors do too.

Brecht wanted neither. His is a thought-provoking narrative theatre where the message is to be recalled (and acted upon in a political sense). He detached actors from their characters, as the Ancient Greeks did, letting their words tell the tale. You can show the difference through roleplay: be a teacher, be a villain, be a teacher, be a fool.

During many lessons in Years 10 and 11 you will have to work on Stanislavski-type, in-depth characterisation techniques, so students get more realistic/convincing work to present for exam and explore issues. But for Brecht, they can adopt stereotypical roles, where we see the actor putting on the part, like an overcoat.

Montage and Episodic

Brecht rejected styles of contemporary and naturalistic theatre, where scenes have to follow in a given order. He preferred a montage effect, where scenes stood alone in any order. In fact, that was a theory; in practice, most of his plays work better in the written sequences.

Today, we are used to seeing montages, collations of action in films and TV ads. Brecht broke new ground with it. Students need to know that he was inspired by Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre with swiftly moving narratives about political and personal events with frequent violence.

Brecht also loved popular entertainment, including American gangster movies, often with narrators and music to move the story along and help the audience to get the point, or moral purpose of the scene.

He also was fond of Japanese Noh theatre, and a quick read of the twin pieces TheYes-Sayer/The No-Sayer are a good start. The plays turn on a moral question: should a sick person be left behind for the greater good? They have sung opening chorus/narration; direct address to audience; stylised staging divided into areas; clear language, no frills; absence of room for emotions.

The Chalk Circle

Next, part of Caucasian Chalk Circle bears study. In groups devise a scene with rough soldiers intimidating peasants, finding a woman hiding a baby which may not be her own. Explain the plot. Use the extract from the Bible on which part of the play is based: 1 Kings 3:16-28, followed by reading the chalk circle scene from the play.

More able students may stick to the script; others will prefer to devise around the idea of harming an innocent by pulling out of a circle, until somebody sacrifices the claim on him/her. Powerful drama, and something of Brecht along the way.

Go off then in a new direction. Groups are friends on some rock climbing expedition, all have to rely on each other. There is an accident, one slips and falls. Play it as straight; then redo it with each character recounting their own role in story; then try it in third person. It will be strange at first, even comical, but it’s fun.

The third person technique is fundamental in creating emotional distance between audience and character. actor and character. Pair work can be helpful here. One is old, infirm; the other is the carer. Do monologues from each where real sympathy (not comedy) is created. Then in third person: the emotion should diminish.

Away from Stanislavski

If they have done work on Stanislavski, it’s possible to summarise the difference between the processes. Stanislavski would say as an actor: ‘Now I am somebody else’; while Brecht as an actor would say” ‘Now I am being somebody else’. For him, actors were ‘demonstrators’.

The shooting from the roof of the dumb daughter Kattrin in Mother Courage is a great scene to have some groups do in Stanislavski style, and others in Brechtian, third person, making strange style. Putting something incongruous on stage is a favourite Brecht technique, to make the audience think.

Brecht used banners and slides of statistics to inform the audience. Arturo Ui, about Hitler, demands a lot of that kind of addition. Modern technology allows for more inventive backdrops, messages and displays to inform the action. Teenagers usually take to that aspect very well.

Other good material for developing distance/making strange is asking directions of a lunatic; telling a friend he/she has a body odour problem; chatting somebody up. Then adapt to third person; put in heavy social message; reveal the attitude of the actors playing the parts.

A couple of films that demonstrate Brechtian theory are I’m Not There (2007) where six actors play Bob Dylan at different ages of his life, including Cate Blanchett; and Dogville (2003) which deploys a chalked outline of a town with minimal props to encumber actors.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Using Theatre-in-the-Round in Secondary School Drama

- First published on Suite 101, Jul 8, 2011

While most school shows, even the sharing in a drama lesson, are done end-on because of the space available, doing it ‘in-the-round’ adds a new dimension.

Many actors and teachers of performing arts fight shy of presenting something where audience encircle performers. Much safer to have them facing a stage, so action can be directed their way!

Some go further, breaking ‘the fourth wall’ of a traditional audience on one side, performers on stage with three sides. Some might curve an audience round a bit. But the really brave will go for a fully rounded spectator area, so that centre of focus is constantly shifting.

The Round Facts

The audience does not have to be literally in a circle, though that can be done. It’s not a circus (usually bigger), though it has similarities. It could be in a square or rectangle. The point is that the audience must surround most of the performance space, leaving one or two gaps for stage access.

This is ideal for intimate performance work, perhaps something where performers want to bring home heavy emotion or comedy. Artaud is done well in this style, as is some Brecht and his followers (Joan Littlewood, John Godber, Caryl Churchill).

Theatre in the round requires little or no scenery, as the audience is the scenery. The fear is often that it can be distracting to see other watchers across the space. But it adds to the intensity. Experience suggests that people actually like the sense of sharing the emotion of the piece with others.

Lighting might be thought a problem. However, limited lighting can be a virtue, depending on the nature of the piece, and a shortage of lights can affect traditional staging just as much. Gobos (light projections) can be done from above. Lighting revolving mirror balls produces amazing effects.

There will be moments of blocking, but in a fluid, well-structured piece, it need be momentary, before the action takes over and actors move, and move again. The stage itself is rarely round. Like a boxing ring, it’s square or rectangular which permits greater use of the space. Street theatre is usually done in the round, as audiences informally gather around the action.

Teaching Techniques

It’s best to let students (or others trying it out) experiment and feel what is natural movement for their characters. Extensively choreographed staging is harder to sustain in this setting. The director should check that every person in the audience can see the face of at least one performer at any one time.

Monologues (and sometimes duologues) can be delivered from the end of the entrance gap to the stage. Sometimes, these entrances are called ‘voms’ (short for vomitorium), which is an unlovely term, but explains the speed which people can enter and exit to heighten the drama. Teenagers will love that one!

If groups of students are not used to round work, warm-up/preparatory exercises are essential. Try doing a short scene between two, where imaginary witnesses are sitting by each wall, and must be appealed to periodically in turn. Then try monologues with imaginary mirrors on each wall (or real ones), so they get used to performing on the move.

In a class situation, there is a ready made audience who can be asked to sit in a circle, a round square, or on 2 sides (traverse) to allow their peers to experiment. It’s that being willing to have a go that marks out the adventurous performer. Even GCSE or some A level practical exam pieces can be presented in this way, with the examiner part of the circle.

Round performance sometimes leads to repetition, from one side, again to another. This isn’t wrong; it should be made a virtue in the devising process. Most students quickly take to the technique, even the less confident improvisers. Many texts also lend themselves to round performance.

The Official Sanction

It all got under way in the 1950s in Britain, when Stephen Joseph’s Studio Theatre adapted a room above a library in Scarborough. In the 1970s, after Joseph’s death, playwright Alan Ayckbourn took it on, frequently writing plays specifically for in-the-round. Others established include the Orange Tree (Richmond), Octagon (Bolton), New Vic (Stoke on Trent) and Royal Exchange (Manchester).

One of Ayckbourn’s productions was Shakespeare’s Othello (1988), and he persuaded English classic actor Michael Gambon to join an illustrious cast. There were two problems, mentioned in Paul Allen’s 2001 biography of Ayckbourn, Grinning At The Edge. One, that Ayckbourn had adapted Shakespeare’s work drastically (as he’s not fond of it); and two, Gambon hated acting in-the-round.

He told Paul Allen: ‘I just couldn’t cope with it. I walked on that stage and gave up before I started. You’re faced, whichever way you look, with a pair of trainers and a different kid wearing them’. Gambon insisted that theatre in-the-round destroyed the player’s secrecy. Ken Stott as Iago had had his part truncated, and he joined Gambon in ‘an angry silence’.

Allen described the resulting performance as ‘terse and immensely gripping’. He said Gambon’s proximity in what was about the size of a living room while he prowled, feeling both caged and exposed was ‘thrillingly dangerous’. So, in that case, the effect of in-the-round was an unintended triumph of intensity and heightened, charged emotion that riveted audiences throughout.

Classic theatre critics have always been divided on in-the-round’s benefits. Kenneth Tynan thought its ‘aesthetic advantages extremely dubious’. Bernard Levin said: ‘the most extraordinary thing about this experiment was its lack of extraordinariness’.

Either way, it’s worth a go with young performers and show attenders, to help broaden their minds to the art of the possible.

Image: Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough, by Daantje Van Delft

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Olympic Games as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Death as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

First published on Suite 101, 9 March 2011.

-

Far from being the last taboo, most teenagers deal with death through drama in a constructive, creative and sometimes therapeutic way. It cannot be avoided.

Drama deals with life’s themes: love, anger, hate, relationships, sorrow, betrayal and, yes, death. Young people lose friends and relatives through accidents and diseases, just as older people do. Children lose parents and grandparents. Thoughtful, compassionate use of human departure can be helpful.

It can be destructive, of course, so care is needed. Where there hasn’t recently been bereavement, dying is such a useful drama technique that it cannot be ignored. It lends itself to comedy too, both intended and unintended.

Quotes are scene-setters, on lesson plans and to teenagers themselves. To demonstrate that death is as old as man, three ancient Greeks, a French speaking Swiss author (1766-1817) and a former French President will suffice, though there are hundreds of good death quotes around.

“Life and death are balanced on the edge of a razor,” (from Homer’s Iliad); “There’s nothing certain in a man’s life except that he must lose it,” (Aeschylus’ Agamemnon); and Euripides: “No one can confidently say he will still be living tomorrow’.” Madame de Stael wrote: “We understand death for the first time when he puts his hand upon one whom we love,” and Charles de Gaulle said: “The graveyards are full of indispensable men.”

Death in Characters

Some good warm-ups are to work in threes on a scene in which one is suddenly removed, leaving the others to continue. Further information is added incrementally: a) the person who left is ill, but expected to return; b) the leaver is now very ill and not expected to return; and c) the leaver dies. What effect do these news items have on the others?

A story from the local paper of recent loss in tragic, absurd/bizarre or suspicious circumstances, is a good starting point for developed drama. This might be at home or abroad. Stories need to go off in different directions, so one strand is of those who leave, the other is of those who stay.

Every action has a consequence, and if each piece of well worked drama requires characters under stress, then an accident or a death provide it. How do characters manage? React with others? Make decisions? How is the plot to be moved on? Cross-cutting scenes help tell a story in non-chronologically order and better dramatically.

Young lives cut short let the “what if” approach have full play. What would this character have achieved if he/she had lived? How does the death move/destroy/encourage/change others? It’s a fact that one person’s tragedy can be an opening for another: taking their job, rebuilding the damage, advising the survivors.

The opportunities for character study and relationships are enormous. If one player is taken out of a teenage drama group (of say, 4, 5 or 6), what next to do with that individual can be a problem, especially if the one who chose to “die” did so only to disrupt others or to have a lengthy period of inactivity.

This is solved by bringing that youngster back into the group as a new character, which in turn develops multi-role skills and pushes plot along. Here is a man who wants to take the woman left behind. Here is a woman who has emerged from the past to claim the deceased was her father.

A Dying Art

In most KS3 and KS4 drama, they stab each other with a knife magically plucked from thin air, and their victim falls in a split-second. The last gasp on the hospital bed can be unconvincing, even comical. Shooting, hanging, poisoning, strangling, guillotining, crushing, drowning and dying of sheer terror are fraught with difficulties.

Most secondary drama requires good mime. Props do not assist this, so work on realistic mimes. It takes time and effort to stab or strangle someone. But the real help is to ask students: do we really need to show the actual death? What is gained by a gang of thugs kicking the victim to death? If it is necessary, work on careful stage fighting techniques.

Use narrator reporting techniques or witnesses telling what they saw; journalistic covering methods of tragedy/news; symbolic deaths; still image sequences and slo-mo deaths. Use lights and shadows. Voices, whispered and built to climaxes make sound collages. Of course, comedy has it’s place, even in death: teenagers enjoy satire and parody, so make the most of it, if appropriate with a given class.

Who has the point of view of the death? A dispassionate observer? A person intimately involved with the person? A killer? A person who caused an accident? The victim him/herself from the afterlife? Experiment, and encourage them to do so by giving each group exercises on different, but convincing, deaths.

Full Research

In their book Teaching Primary History (1997), John Fines and Jon Nichol demonstrated how to become a teller of historical stories to children. The same principle applied to secondary. John Fines told stories, always asking students “to respond and develop their own understanding of history, causes and consequences, young and old people.” That meant deaths, too.

In past times, not only was life brutal, it was relatively short and painful. If historical accuracy is part of the learning, research infant mortality, large families, economic struggles to survive and the age of maturity in the past.

Students may have siblings serving in conflicts overseas. Wars that parents, grandparents or other relatives have been involved in are rich in facts to support creativity. The internet is loaded with statistics, biographies and stories for devising. It needn’t all be true when they understand that fact and fiction mixed make faction, the essence of drama.

It’s said people are more moved by the hurt to an animal than a child. Local media report animal cruelties, all of which can be good stimulus material for KS3 and both Y10 and Y11. Treat animal death as human death, sensitively.

One safe way to deal with the topic, if a teacher is worried, is to play, interacting with students, in role. Take the lives of famous people who died young: celebrities, actors, musicians and use their actual stories to create some docu-drama. If it all seems like a soap opera, so be it. It’s all drama.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Holistic Approach to Teaching Secondary Performing Arts

First published on Suite 101, 2 March 2011

-

At Key Stage 3, 4 or 5, a fully integrated arts background introduces students to the joys of dance, drama and music combined as the performing arts.

Some practitioners, and therefore students, have long been under the misapprehension that there is a purity in separate arts forms to be studied as discrete subjects. Any young person nowadays seeking a career in entertainment may have to sing/dance according to role, and as more arts evolve from fusions, the days of separateness may well be gone.

Performing Arts is a Partnership

In musical theatre, circus, carnival, pantomime, variety, art forms work in partnership, feeding off and into each other. If performance tells stories, then the choice of art forms is the richer for being broader. Polish Director Jerzy Grotowski said: “Do not think of the vocal instrument itself, do not think of the words, but react.” He could have been speaking to dancers too; even to an orchestra. React; interpret; perform.

In his book A Shared Experience: The Actor As Storyteller (1979), Mike Alfreds wrote: “tell a story using gestures for illustrating, commenting, responding and contacting; tell a story using sounds and use first person narration.” It’s a small step towards integrated performing arts.

Tim Etchells, in Certain Fragments (1999) wrote about making new texts for performance in collaborative processes, opening up writing for performance beyond just plays. He put words seen and read on stage, lists, physical action, whispering, collage, stories and speculations: “a text of lines from half remembered songs, a love letter written in binary, a text composed of fragments.”

Key Stage 3: Using a Musical

Once the teacher sees how art forms collide, merge, slide over, absorb other forms, the next step is imparting the excitements of that continuous rediscovery to students. Key Stage 3 is a good place to begin, and this can be in Y7, Y8, Y9 or spread across all three years. In schools where dance, drama and music departments work in harmony and teach accordingly, it’s easier.

Even when timetables make collaboration difficult, any one subject can show how linked to the other two it is. Take a musical, say West Side Story, but in drama don’t admit that yet. Start with some themes from Romeo and Juliet: hostility between two families; how that plays out over the years so the original reason is lost. Then, the unthinkable, a teenage boy from one family falls in love with a teenage girl from the other.

The prologue, dramatised in the opening sequence of the 1961 movie, is beautiful, inventive, clever and watchable harmony of choreography and music. Individual characters lead to dramatic studies and conflicts. Again, music from the musical through the movie, demonstrates how a performer can express any emotion through acting, dancing or playing music.

Other themes like arranged marriages, reckless/fecklessness of youth, accidents that happen in fighting, wasteful tragic loss of young life to achieve nothing, all can be seen, heard and grasped. By the end of a term’s study, most students should see how the arts come together in musicals.

Using the same approach to some or all of Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, The King and I, Barnum and Hair, the point can further be reinforced. More modern musicals like We Will Rock You, Mamma Mia, Jersey Boys use pop music which should be instantly appealing to launch the learning.

Key Stage 4: The Exam Constraints

GCSE, BTec and other exams can further open integration and understanding. Much KS3 learning is still applicable: a musical uses integration to tell a story, convey a message and to entertain. These skills are needed in Y10 and Y11 exams, equally.

Most schools stage a show at least once a year. A full musical is within the realms of (hardworking) possibility for most teams. Even a variety show, devised compilation and play with music can be spiced up with art form integration. Take the Music Hall genre: useful for social and theatrical history, outrageous variety including comedy and harnessing discrete art forms shamelessly together.

In exams, where students have to create/devise/compose their pieces, looking at exponents who tell stories (Bob Dylan, Steve Reich, Bertolt Brecht, John Godber, Christopher Bruce) shows that material is taken from everywhere; found music (produced already by others) or improvised/original. Dance and drama work can be derivative, but always benefits from practitioner stimulus.

Key Stage 5: A Level and Beyond

OCR Performance Studies course shows how performing arts are the 4th art discipline incorporating dance, drama and music through the study of a wide range of practitioners. Theory and practice share syllabus space and teaching time. Discrete arts are the order of the day in other single A levels, but in school shows, outside productions sixth formers get involved in, their wide interests in modern music and dance, fashion and technology, help teach them arts integration.

Clive Barker in his book, Theatre Games (1977), said that actors’ work was categorised: real physical/vocal skills, mimetic skills, imaginative exploration, non-natural behaviour patterns while interacting with other performers/characters and audience. There is no difference in essence between actors, musicians and dancers’ purpose, just different skills.

Years ago sixth formers had compulsory art and music appreciation sessions, irrespective of their studied subjects. The broader college and university courses still appreciate young people acquiring understanding of how arts dovetail. No artist works in a vacuum. Contemporary times/events, moods, tragedies and what others have already created/painted/danced/composed/acted, do influence any work of art.

To neglect or fail to appreciate that, is to do a disservice to tomorrow’s generation of performers and audiences. More people benefit from understanding context, grasping history to some extent and appreciating a rich, vibrant arts world. The painter Marc Chagall said: “For me a circus is a magic show that appears and disappears like a world. It is profound.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Soap Operas as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

First published on Suite 101, 25 February 2011

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Neighbours-at-War as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

First published on Suite 101, 23 February 2011

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Six Degrees of Separation as a Secondary Drama Teaching Tool

First published on Suite 101, 23 February 2011

To teach teenagers about characterisation in drama, the notion that everyone on Earth is no more than six steps from any other, is a useful device.

Drama students in their teens often struggle moving from straight role-play (be a police officer, be a dad, be a shopkeeper) into characterisation that develops better drama and higher grades. The interconnectedness of human beings also drives home the smallness of the world, and teaches something of humanities.

Certain universal truths arise in drama. People speak about a “friend of a friend” who told them something, some rumour, hot tip or gossip. A few quick “Chinese whisper” type warm-ups should set the scene effectively.

The Shrinking World

Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy published a story, Chain-Links (1929), in which the world was “shrinking” due to peoples’ ever-closer connectedness. This became “network theory,” touching sociology, mathematics, physics, politics, travel, communications and the World Wide Web. A chain is any people thread in business, neighbourhoods and “friends.”

In the story, characters created a game in which an individual could contact any other on Earth anywhere using no more than five others. The work of social psychologist Stanley Milgram published in 1978 formally articulated the “mechanics of social networks.”

Six degrees of separation have become the small world phenomenon. Milgram suggested human society is a small world network of short, human-found path lengths. Ease of global transport, instant telecommunications and news contribute to the notion that the world is, in effect, getting smaller. The internet confirmed it. In 2001 Columbia University’s Duncan Watts ran internet experiments using an email message, and discovered the average person was part of an interconnecting line of six senders.

The continuing evolution of networking technology means that the age of experiments/theories is over. Now it inspires artistic and cultural pursuits.

Games, Films and Things

Historical background may of limited interest to students, but puts it into context for the drama teacher. When you talk about “online,” you have their interest. The Digrii Project allows anyone to connect with others, online. The Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon is an online game based on Bacon’s assertion that he’s “worked with everybody in Hollywood.” The objective is to link actors to Bacon through no more than six links.

In 2007 Milgram launched SixDegrees.org, a charitable social network that allows celebrities to raise funds for their favourite good causes. These include Nicole Kidman (UNIFEM), Robert Duvall (Pro Mujer) and Jessica Simpson (Operation Smile). He wanted to bring “social conscience to social networking.”

John Guare wrote a play on the six degrees premise in 1990, developed into a movie in 1993, starring Stockard Channing, Will Smith and Donald Sutherland. Wealthy New York art dealers took in a plausible man claiming to be a son of Sidney Poitier and friend of their son and daughter. He turned out not what he seemed; everyone re-evaluated their lives.

2006 US TV series Six Degrees used six workers’ lives, while Lost (2004-10) exploited characters’ connections. TV travel show Lonely Planet Six Degrees explored cities through locals who introduced others to continue the tour.

My Date With Drew (2004), intertwined characters in Babel (2006), and the sexual exploit links in TV series The L Word (2004 onwards) harnessed the dramatic possibilities of people linked, as did US TV pilot, Six Degrees of Martina McBride.

It was used in a Belgian TV news serious, and Six Degrees of Shafer appeared in a video game, Brutal Legend. The web experiment 6 Degrees of Sesame saw a man link his girlfriend with Sesame Street’s founder; Full Circle, a song by No Doubt refers to separation by six steps.

Stuart Maconie’s BBC 2 radio show has a quiz linking artists and songs. Websites include: SixDegrees.com (1997-2001) an early Facebook, listing friends and acquaintances by degree away. LinkedIn runs on the six degrees principle passing messages to friends in order. Nootrol does the same, linking businesses in a carbon chain.

Six Degrees of Wikipedia and Twitter are similarly structured. Facebook itself, the most successful social global network to date, harnesses it and will be familiar to all students. Indeed, character profiles on network sites are good starts for character building in drama.

Facts and Fictions

As drama integrates fact and fiction (faction), whether the six degrees theory works, is irrelevant. US Primetime TV in 2006 set up an experiment run by Professor Duncan Watts from Columbia University in a race for people to connect themselves to a random third person in the fastest, most unusual ways.

The Small World Project assigned searchers random targets around the world to whom they had to link by email, by connecting a human chain. 60,000 people from 170 nations took part, completing chains in an average six links, thus supporting the theory. That in itself is a good start for a piece of drama.

Even better, is to get students to choose their six unconnected characters, decide some background (how old? works? lives where, with whom? ambitions? fears? favourites? dislikes? relationships?). Then find logical but remote connections. Two once attended the same concert. Two were at same primary school. Two were on a bus station, unbeknown to each other at the time.

Almost immediately, a web of random connectives are created. There’s no limit. Characters are immediately invested in interesting, meaningful lives in deeper drama where tensions arise between and among.

If they need a starting point, try: a train travelling between Stations A and B; passengers are together for the duration of that short journey but never again. At the next stop, some leave, newcomers arrive.

Then they go off into their lives. See what happens? Chance is harnessed to make drama, a soap opera unfolds. It links with KS 3 drama, but particularly with UK KS4, and devising materials as almost everything does.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Drama Devising Themes for Years 10 and 11 in Performance Exams

First published on Suite 101, 22 January 2011

Using themes to suggest improvisation ideas whilst employing the various drama strategies and elements, is best way to develop Key Stage 4 drama into exams.

The final unit of Edexcel Drama GCSE that started teaching in September 2009, incorporates all earlier learning into an assessed performance. By the time this stage is reached, Y11 students have acquired some of the processes of drama, explored and experimented with techniques and developed ideas.

The final exam requires build-up by devising and rehearsing, group decision-making and polishing of skills. Other exams boards expect similar, in order to complete the drama-making experience at this level. Edexcel produces an assignment brief annually for guidance.

An overall theme is chosen, such as loss, rage, love, prejudice and fear. Students may devise from stimulus, present a short published play, an extract from a longer published play, adapt scenes from a published play, use text/characters/plot from a published play and add improvised material, a Theatre-in-Education piece or devise with added poetry, songs and factual material.

Approaching the Devising Process

The overarching theme is simple enough. The harder part is gathering material and prompting students in the directions of research that will feed into their pieces. The teacher needs to prepare this carefully in advance. The earlier parts of the course should help.

Themes are useful from the outset of Y10: old age, characters under stress, horror, body, departures, missing, interrogation, Big Brother (from Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four), commedia dell’Arte, melodrama, surrealistic viewpoint, madness, nightmare and generational conflict. Each topic will have required a stimulus, such as poem, newspaper cutting, song, music, painting, play extract, film clip, court evidence or diary/letters. The principle is the same for the performance exam.

Once the actual theme is announced, the teacher puts students into groups of five or six, but much depends on behaviour, relationships and friendships and the need in comprehensive teaching to mix abilities thoroughly. As candidates are marked individually not collectively, that should help.

Each group should be steered into a particular research approach, depending on individual and combined abilities, interests and energies. There are plays and films to find around or about the theme. Each group should come up with a different one to inspire character work, especially if they understand the basic structure of protagonists in conflict, under stress and the crisis/turning point, and the links that bind people.

Other stimulus materials, like songs and lyrics, pieces of music, documentary evidence, photos and paintings come next. Different ones for different groups. That way, the whole class is still on the same theme, but is tackling it in different ways. There is, therefore, an element of competition which usually arrives in any case, and is no bad thing to sustain interest and build team spirit/loyalty.

Building a Timetable

The exam is available from April to the end of May, so if work is started in the spring term, they have about 8-10 weeks of lessons researching, devising and rehearsing. It’s vital that a limit is placed on the early phases. Do not allow them to sit around lesson after lesson talking about ideas and the pointers the teacher has given.

Limit time at computers, researching. Set frequent slots for sharing with teacher (and some with their peers) a given idea, angle or character doing something. Video everything, so they see for themselves what needs to be done to make it a performance. The experimental drama phase was earlier; now the audience (and the examiner) is paramount.

Insist they complete planning, writing, editing at one date; all blocking moves, proxemics and decisions about audience seating, entrances/exits, use of techniques (still images, thought-tracking, narration, physical theatre) by another date. There must be enough time to rehearse, so it is polished. Again, filming rehearsals so they can make self-critical judgments is helpful.

With Edexcel, students can choose technical support instead of performing. So, a group could have somebody doing lighting or sound, costume or props, or design attached to them, part of the team making a performance. If that doesn’t happen, ensure they don’t get obsessed with peripherals like what they are wearing and which spotlight is where.

The most exciting work takes the Brechtian view: the message is more important than the theatrical furniture. Perhaps no lights, a bare space, even an unusual place with minimal or no props is best. Miming is crucial to create the essence of the piece, and props can get in the way. Physical performance, being the door, the chair, the lamppost as well as the people, is a further challenge that can reap marks.

The Final Fortnight

A ‘dress rehearsal’ is a given, and should be placed at a time relative to the exam date to allow enough hours to work on glaring errors. One idea is to stage all groups performing in the order that they will do on the exam day(s), and have them marked according to exam criteria by the teacher. The exam must be filmed for the examiner to take away, so this rehearsal should also be.

When the teacher gives the critique, the evidence is there for all to see. Some teachers like to mark this at the tougher end of the scale, in order to encourage students in their final push. The natural psychology of the teacher takes over: some students benefit from feeling they have fallen short two weeks off; others need all the encouragement and coaxing possible.

Just as GCSE is a stage in the process for children and young people from SATs tests, GCSE, A level or BTEC, university/training and into lifelong learning, so the drama course itself is a learning journey. Themes used in Key Stage 3 drama, and developed further in Year 10 and in the assessments of Year 11 can be revisited and extended.

Theatre-in-Education is a challenging way of exploiting themes, issues, ideas and feelings through some local history, personality or event to illustrate the exam theme. Verbatim Theatre is another stylistic approach, taking evidence from witnesses and those who experienced something first hand to tell a story through their own words. Whichever style each group is encouraged to adopt, the main thing is help students realise that nothing is ever wasted. Every pain, happiness, hope, fear, expectation, betrayal is the stuff of drama, as of life. Just look at soap operas!

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Theatre-in-Education Teaches, Educates, Entertains & Challenges

First published on Suite 101, 18 December 2010.

TiE is a specialist genre combining teaching ‘in drama’ with teaching ‘through drama’, believing theatre is a common language that should be open to all.

TiE is a specialist genre combining teaching ‘in drama’ with teaching ‘through drama’, believing theatre is a common language that should be open to all.

Theatre-in-Education is a concept, more than simply combining elements of theatre in an educational point. It is a device to research an issue, present an argument or several views, and to make children and students aware of the teaching aim through drama. Along the way it awakens love of interactive performance.

It “looks at Reality through fantasy with the eyes of a child. TiE employs theatre elements as ‘primary’ teaching-learning tools; educating all levels of intelligence, young and adult, focussing on academic advancement of the ‘slo learner’.’’ This view of the concept, from Belle Branscombe from Theatre In Education in the USA, where it is primarily of benefit to help those with different and challenging learning abilities, is but one perspective.

Peter Sloth Madsen, from Denmark, who has worked theatre in education in Mozambique said: “theatre is used as a respected and acknowledged educational tool worldwide.” He has produced an “edutainment” DVD supporting his practical work, effectively using theatre to educate. TiE is professional actors working with children to teach about something other than theatre skills.

The Origins of TiE

It began in Britain in the 1960s with the pioneering work at the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry. By the mid 1970s, most repertory companies had their own catalyst-resource companies, funded by the Arts Council and/or local education authorities. Greenwich Young People’s Theatre (GYPT), Bolton Octagon Theatre and the Crucible, Sheffield were among those that built national reputations. Some were purely touring, some based in one place, others did both.

Children’s theatre companies are purely entertainment focussed. TiE is education/performance-based, dealing with issues of interest/concern to children and adults, maybe with a political, social or local historical dimension. Workshops are part of the TiE approach, usually run by the company with participant audiences afterwards. These give an opportunity for the issues to be explored in a different way, perhaps by “hot-seating” a character, or leaving the material planted firmly for teachers to follow up once the company has moved on.

Companies employ cross-curricula approaches, but some specialize: Molecule Theatre used to work on science education; a company explored the history of the English canal system; Victorian factories and child labour were frequently used. Christianity or Shakespearean text inspire some; dangers to the environment and road safety are common themes.

Methods, Ideas and Material

Starting with educational topic or debate and developing a show around it, leads some to work always with particular age group or Key Stage in mind. Oily Cart works with students with multiple learning difficulties. Typically, TiE is done with a class or two, maybe no more than 40 children. Characters might work with them as a preamble, setting up situations, creating participation in advance (like factory workers, slaves, a jury, local councillors). Children may also be given in-role functions in the drama to come, and arguing with or opposing a character is popular.

Often TiE works are scripted, but normally after the run. Stories and narratives are improvised, taking account of audience participation and unexpected responses, so several degrees of flexibility are mandatory. Experience shows children very quickly suspend their disbelief and take each actor as real. They actively join in “hot seating.” to put a character on the spot about his/her motives and actions, both within performance and workshop.

Still images or “depictions” or “tableaux” present pictures. Theatrical images can be more powerful than words. It’s important in TiE that emotions and passions are stirred in order to heighten the learning that is the reason for the piece. Some historical or imagined stories are compelling in their own right and lend themselves to performance in any genre. Other pieces of TiE are arrived at from plot fragments, letters, court evidence, artifacts, photographs, newspaper reports, witness statements (now known as “Verbatim Theatre”).

Themes from the UK or abroad (South Africa during apartheid; Amazonian rain forests; colonization) have been starting points. The smallness of the world. Mental illness or handicap, the treatment of women in a particular time and place, planning laws, big business or prejudice may arise as driving forces, to inspire gathering of material and ideas to support devising. Either way, extensive research is a hallmark of creating TiE.

Community Theatre

Community theatre companies and TiE share some common ground, targetting particular social groups. According to TeacherNet: “Cardboard Citizens work with homeless and ex-homeless people, while Clean Break with female ex-prisoners. However, they go further than TiE companies, in that they usually carry out training projects for adults, e.g. helping women back to work.”

TiE often tackles political issues. In that sense, it’s a branch of political performance that ranges from street theatre through to interactive theatre. It’s in the box of tricks teachers can employ, like Teacher-in-Role, as they develop curricula. An element of TiE is useful in Key Stage 3 drama, and powerful in extending work in Year 10 and in GCSE exam Year 11.

Whatever approach, theme or story a TiE company employs, the fact that performers work closely with children and teenagers in creating theatre is invaluable for youngsters for whom live performance is a rarity. TiE is theatre and learning that stays in the mind for years. The arts ask no more; education demands it; youngsters deserve it.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Drama Teaching Ideas and Plans for Year 11 Lesson

First published on Suite 101, 15 December 2010.

-

Image: Drama practicals may be on a formal stage or not.

Image: Drama practicals may be on a formal stage or not.

The end of Key Stage 4 GCSE Drama sees the arrival of various assessments, from written evidence of learning to practical applications in performances.

Exam boards offering GCSE Drama are flexible enough to allow some units to be taken during Year 10. Many schools, however, opt for examining in the final year, believing most students need longer to prepare their work and complete supporting evidence. They see Y11 as simply the second (shorter) half of a two year programme.

Students have learned to use drama strategies, like still images, thought-tracking, marking the moment, hot-seating, narrating within and without a story, cross-cutting and perhaps tried forum theatre, where the audience or performers change their focus for them, mid-performance. They have used a wide variety of stimuli, including play extracts, songs, music, live shows, TV and recorded pieces, newspaper stories, photographs.

They have exploited the potential for dramatic development of themes, ideas, issues and feelings using mime,sound, lighting, masks, costume, space, levels, gesture, voice and movement. They have discovered elements like action and plot, drama forms, rhythm and pace, contrasts, conventions, characterisation and symbols.

Exploration of Drama